산업연관분석을 이용한 수소경제의 경제적 파급 효과 분석

2023 The Korean Hydrogen and New Energy Society. All rights reserved.

Abstract

The Korean government is actively promoting the hydrogen industry as a key driver of economic growth. This commitment is evident in the 2019 hydrogen economy activation roadmap and the 2021 basic plan for hydrogen economy implementation. This study quantitatively analyzes the economic impact of the hydrogen economy using input-output analysis based on the Bank of Korea's 2019 input-output table, projecting its size by 2050. Four parts dealt with production-inducing, value-added creation, employment-inducing, and wage-inducing based on a demand-driven model. The results reveal that transportation had the most remarkable economic effect throughout the hydrogen economy, and production was the least. The hydrogen economy is projected to reach 71.2 trillion won by 2050.

Keywords:

Hydrogen economy, Input-output approach, Demand-driven model, Economic impact키워드:

수소경제, 산업연관분석, 수요 유도형 모형, 경제적 효과1. 서 론

화석연료 사용으로 배출된 온실가스로 인해 기후변화는 가속화하고 있다. 이에 대응하여 전 세계 국가들은 저탄소 에너지원을 찾고 있다. 2021년 11월 영국 글래스고에서 개최된 유엔 기후 변화 협약(United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, UNFCCC) 제26차 당사국 총회(26th UN Climate Change Conference of the Parties, COP26)에 참가한 국가들은 지구 평균 기온 상승 폭을 산업화 이전 대비 1.5도 이내로 제한하는 목표에 합의했다. 이 목표를 달성하기 위해서는 전 세계 2030년 온실가스 배출량이 2010년 온실가스 배출량의 45%까지 줄어야 하며, 2050년에는 0%가 되어야 한다1). 수소는 연소 과정에서 온실가스가 배출되지 않으므로, 그 목표를 달성하기 위한 하나의 수단으로 수소에너지가 주목받고 있다2-6). 화석연료는 매장량이 한정되어 있고 환경오염을 초래하기 때문에 현재와 미래의 에너지원은 수소에너지와 연료전지 등이 포함된 신에너지와 우리가 흔히 알고 있는 풍력, 조력, 수력 등 재생에너지로 점점 변화하고 있다. 그중 수소에너지는 기체, 액체 형태로 수송 및 저장이 용이하며, 수소를 생산하는 원료인 물이 지구상에 풍부하기 때문에 앞으로 핵심이 될 청정에너지원 중 하나로 꼽힌다.

따라서 세계 각국은 기후 변화 대응을 위한 중요한 정책 과제 중 하나로 수소경제의 활성화를 제시하고 있다. 국제에너지기구(International Energy Agency, IEA)에 따르면7), 2019년까지 한국을 포함하여 3개의 국가만이 수소경제 육성 계획을 만들었다. 그러나 2021년까지 총 17개의 국가가 수소경제 활성화 전략을 수립하고 발표했으며, 20개 이상의 국가가 전략을 수립 중이다. 특히 2022년 8월 미국 의회를 통과한 인플레이션 감축 법안(inflation reduction act, IRA)은 청정수소에 대한 정부의 금전적 지원 방안이 포함되었다. 또한 유럽연합(Europe Union, EU)은 금년 4월 ‘REPower EU Plan’에서 청정수소의 생산 목표를 대폭 상향했다.

이러한 국제적 흐름에 한국도 예외가 아니다. 2019년 1월, 한국 정부는 수소경제 활성화를 위한 청사진인 ‘수소경제 활성화 로드맵’을 발표했다8). 이 로드맵은 수소경제의 가치 사슬별 달성 목표를 설정하고, 목표 달성을 위한 추진 전략과 15개의 세부 과제를 담고 있다. 이 로드맵이 성공적으로 실행된다면, 2040년 에너지 총 소비량의 5%가 수소로 충당될 수 있을 것으로 기대된다.

한국은 수소경제 활성화의 법적 근거 마련을 위해 2020년 2월 “수소경제 육성 및 수소 안전관리에 관한 법률(이하 수소법)”을 제정했다. 저자들이 아는 범위 내에서, 수소경제 활성화를 위해 만들어진 법률은 현재 한국에만 존재한다. 수소법은 크게 세 가지 주요 내용을 담고 있다. 첫째, 수소 가격 책정 체계의 투명화이다. 둘째, 정부가 산업단지, 물류 센터 등의 운영자에게 수소충전소를 건설하도록 요청할 수 있다. 셋째, 수소의 안전 관리 체계를 강화한다. 수소법 제정 이후, 국내 15개 대기업은 Korea H2 Business Summit이라는 협의체를 만들고, 2030년까지 수소 산업에 총 43조 원을 투자하겠다고 선언했다. 2023년 현재 이 협의체에 소속된 17개 기업은 투자 규모를 50조 원 이상으로 확대할 계획을 세우고 있다.

한국 정부는 수소경제가 일자리를 창출하면서 경제 성장에 기여할 것으로 기대한다. 그러나 사실 앞으로도 상당 기간 기업들이 수소 관련 사업에서 이윤을 얻기는 쉽지 않을 것이다. 아직 한국에서 수소의 생산, 저장, 운송, 활용 등과 관련한 가치사슬이 제대로 구축되지 않았기 때문이다. 예를 들어, 수소를 생산하더라도 인근에 수요처가 없는 경우가 많다. 또한 수소충전소 설치 및 운영 사업은 정부의 보조금이 없다면 수익성을 확보하기 어렵다. 물론 초기 인프라 투자는 단기적으로 수익성 악화를 야기할 수 있지만, 장기적으로는 연관 산업의 생산 활동을 촉진하여 고용 및 소득 증가와 수요를 창출하여 경제 성장에 기여할 것이다. 결국 정부는 수소산업의 활성화를 위해 당분간 막대한 재정을 투입해야 한다. 이에 민간 기업들 또한 기술 개발과 전문 인력 양성에 대규모 자본을 투자할 계획이며, 그 투자에 따른 경제적 파급 효과에 대한 정량적인 정보가 필요한 상황이다.

본 연구에서는 산업연관분석을 이용하여 수소경제의 경제적 파급 효과를 분석하고 2050년까지의 수소경제의 규모를 추정한다. 산업연관분석은 수소와 관련된 다양한 주제 분석에 널리 사용되었다9-15). 예를 들어 Lee 등16)은 2040년까지의 미국과 중국의 바이오 수소 산업 투자의 경제적 효과를 검토하였으며, Chun 등17)은 2020년부터 2040년까지 한국 수소 R&D 투자의 경제적 효과를 분석했다. 하지만 2050년까지의 수소산업 부문의 규모를 예측하고 경제적 효과를 분석한 사례는 찾아보기 어렵다. 이러한 점에서 본 연구는 관련 문헌에 기여할 뿐만 아니라 정책결정자들에게 정량적으로 유용한 정보를 제공할 것이다. 구체적으로 살펴보면, 본 연구에서는 2019년 투입산출표를 이용하여 한국 수소경제의 경제적 효과를 분석한다. 또한 2030년, 2040년, 2050년 3개 시점의 수소경제 규모를 예측하고자 한다.

2. 수소경제 활성화 로드맵의 개요

정유와 석유화학은 한국의 대표적인 주력 산업이다. 이들 분야에서 생산된 제품은 기술 및 가격 경쟁력을 확보하고 있어 절반 이상이 해외로 수출된다. 아울러 전국적으로 천연가스 배관망이 깔려 있으며, 수소차와 연료전지가 국내에서 생산되고 있다. 한국 정부는 2018년 8월 지속 가능한 성장을 위한 3대 전략투자 분야 중 하나로 수소를 선정하였다. 이와 더불어, 수소가 화석연료를 대체하면서 고용과 부가가치를 창출하는 주력 분야 중 하나로 자리매김할 수 있도록, 수소경제라는 미래 비전이 설정되었다. 수소경제를 구체화하고자 정부는 정책 결정자와 민간 자문가로 구성된 ‘수소경제 추진위원회’를 설립하고, 2019년 수소경제의 미래상을 담은 ‘수소경제 활성화 로드맵’을 발표했다. 이 로드맵의 가장 중요한 목표는 한국이 수소차와 연료전지를 중심으로 2040년까지 세계 최고의 수소경제 선도 국가로 도약하는 것이다.

로드맵에 제시된 2040년까지의 수소경제 추진 전략은 크게 3단계로 구성된다. 첫째, 수소경제 준비기(2018-2022)에는 산업 생태계 조성을 위한 법적 기반 마련, 중소기업의 수소산업 진입 지원, 생산 기술의 국산화라는 3가지 목표가 수행될 것이다. 둘째, 수소경제 확산기(2022-2030)의 3대 주요 목표는 가정 및 건물용 연료전지 보급, 수요 증가에 대비한 안정적인 공급망 구축, 그린수소 생산 전환이다. 셋째, 수소경제 선도기(2030-2040)의 4대 과제는 탄소 없는 에너지 수요 및 공급의 순환 시스템 확립, 수소 가격의 안정화, 해외에서의 수소 생산, 수전해를 통해 생산되는 수소의 상용화이다.

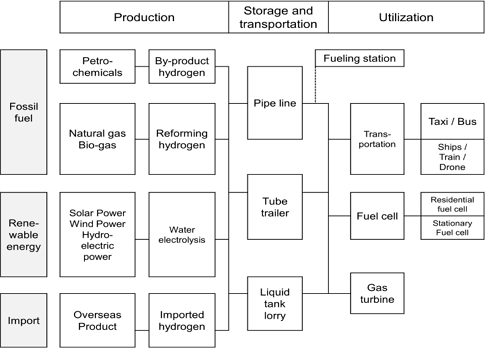

Fig. 1에 제시된 바와 같이 정부는 수소경제의 가치사슬을 생산, 저장, 운송, 활용의 4단계로 식별하였다. 구체적으로 보면, 수소 생산에 ‘화석연료의 개질’, ‘재생에너지를 활용한 수전해’, ‘해외에서의 수입’의 3가지 방법이 사용될 수 있을 것이다. 현재 한국에서 사용되는 수소는 대부분 화석연료 개질과 정유 및 석유화학 공정에서 생산되는 부생 수소이다. 따라서 정부는 향후 탄소 포집 장치를 부착하여 온실가스가 배출되지 않는 천연가스 개질수소 생산 및 재생에너지를 이용한 수전해 방식으로 수소 생산 방식을 전환할 계획이다. 수소의 저장 및 운송 수단으로는 파이프라인, 고압 기체 수소를 운반하는 튜브 트레일러, 액화 수소를 운반하는 탱크로리의 3가지가 추진되고 있다. 국내에서 수소가 생산되는 장소는 한정되어 있으므로, 수소를 압축하여 저장 및 운송하는 기술의 확보가 향후 수소산업의 수익성에 영향을 미칠 것이다. 수소가 활용되는 분야로는 모빌리티, 가정용 및 건물용 연료전지, 발전용 연료전지, 수소 터빈 등이 고려되고 있다.

수소 활용의 대표적인 분야는 모빌리티와 연료전지로 예상된다. 이에 수소경제 활성화 로드맵에서는 수소차의 보급 목표를 2018년 1만 8천 대에서 2022년 8만 1천 대, 2040년 620만 대로 설정하였다. 2040년의 목표는 승용차 590만 대, 버스 6만 대, 택시 12만 대, 화물차 12만 대로 구성된다. 이와 더불어 수소 충전소(hydrogen-fueling station)는 2018년의 14개소에서 2022년 310개소, 2040년 1,200개소로 늘어날 것이다. 발전용 수소 연료전지는 2018년의 0.3 GW에서 2022년 1.5 GW, 2040년 15.0 GW로 확대될 것이다. 이 목표를 달성하기 위한 수소 공급량은 2018년의 13만 톤에서 2022년 47만 톤, 2040년 526만 톤에 이를 것이다. 수소의 가격은 2018년 kg당 8,000원에서 2022년에는 6,000원으로 인하되고 2040년에는 3,000원 수준에 도달할 것이다.

3. 방법론

3.1 산업연관분석의 개요

산업연관분석은 일정 기간의 산업 간의 재화와 서비스의 흐름을 기록한 통계표를 이용하여 산업 간의 관계를 정량적으로 나타내는 방법이다18). 산업연관분석은 투입산출분석이라고도 한다. 이것은 산업연관분석이 근본적으로 상호의존성, 즉 국가경제 내 산업들이 생산 및 수요 활동을 통해 유기적으로 연관되어 있음을 전제로 하기 때문이다19).

다만 수소경제 관련 부문은 투입산출표에 명시되어 있지 않으므로, 본 연구에서는 선행연구에 따라 기존의 투입산출표에 수소경제 관련 부문을 추가하여 분석하였다10,14,16,20). 3절은 산업연관분석의 적용 절차에 대해 다루며, 투입산출표에서 수소경제 관련 부문을 식별하는 방법은 4절에서 설명한다.

3.2 수요 유도형 모형(demand-driven model)

i부문에서 생산되는 재화의 총산출 Xi는 중간 수요 Zij 와 최종 수요 Yi의 합으로 구성되며, 식 (1)과 같이 표현할 수 있다.

| (1) |

여기서 aij는 투입계수(input coefficient)라 한다. 투입계수란 특정 부문의 총 산출 대비 그 산업의 한 단위 생산을 위해 투입되는 중간 투입의 몫을 의미한다. 투입계수는 어떤 부문 또는 산업의 최종 수요 변동이 다른 부문의 생산 활동에 미치는 생산 유발 효과를 측정하는 데 사용된다. 그러나 부문 수가 증가하면 투입계수를 이용하여 생산 유발 효과를 일일이 측정하는 것은 불가능하므로, 다음의 계산식이 적용된다.

| (2) |

투입산출표의 총 산출은 중간 수요와 최종 수요의 합으로 이루어진다. 식 (2)는 식 (1)을 행렬로 표현한 것으로 수요 유도형 모형(demand-driven model)이라 한다. (I-A)-1은 레온티에프 역행렬(Leontief inverse matrix), 투입 역행렬(input inverse matrix) 또는 생산유발계수(production inducement coefficients)라 한다. 식 (2)는 특정 부문에서 최종 수요가 한 단위 증가하였을 때 직간접적으로 유발되는 다른 부문의 생산량을 의미한다21).

수요 유도형 모형을 이용하여 계산한 총 산출액은 특정 산업이 자기 부문에 스스로 미치는 영향을 포함한다. 따라서 수소경제가 경제 내 다른 부문에 미치는 영향을 정확히 평가하기 위해서는 수소경제 관련 부문이 외생 부문으로 분류되어 최종 수요에 포함되어야 한다22). 이렇게 분석 대상을 투입계수행렬에서 분리하는 과정을 외생화(exogenous specification)라 하며, 이하 계산식에서는 위첨자 ‘e’로 표시한다17).

생산 유발 효과는 특정 부문에서 한 단위의 생산 또는 투자가 다른 부문의 직간접적인 생산량을 얼마나 증가시키는지를 나타낸다. 편의상 특정 부문은 K 부문으로 표시한다.

| (3) |

식 (3)에서 (I-Ae)-1는 K 부문에서 최종 수요의 한 단위 발생에 따라 다른 부문에 유발되는 직간접적인 생산 유발 효과의 합계이다. 는 투입계수행렬 A에서 K 부문을 제외한 행렬이다. XK는 K 부문의 총 산출이다.

부가가치 유발 효과는 특정 부문의 한 단위의 생산 또는 투자를 통해 발생하는 다른 산업의 부가가치 변화량을 의미한다. 부가가치계수는 부가가치액을 최종 수요로 나눈 것으로, Av = Vi/Xi로 정의된다. 부가가치계수 행렬에서 K 부문에 해당하는 섹터를 제외한 후 대각 행렬로 전환하여() 식 (3)에 곱하면 식 (4)와 같이 표현할 수 있다.

| (4) |

여기서 Δ Ve는 K 부문을 제외한 다른 부문의 부가가치 증감량, 즉 부가가치 유발 효과를 의미한다.

임금 유발 효과는 특정 산업에서 한 단위의 생산 또는 투자로 경제 전체의 임금이 얼마나 변동되는지를 나타낸다. 임금계수는 Aw = Wi/Xi로 정의된다. K 부문을 제외한 임금계수 행렬의 대각 행렬을 식 (3)에 곱하면 식 (5)가 산출된다.

| (5) |

Δ We는 K 부문을 제외한 다른 부문의 임금 변화분을 의미한다. 또한 는 임금유발계수 행렬에서 K 부문을 제거한 후 대각화한 행렬이다.

취업 유발 효과는 특정 부문에서 10억 원의 생산 또는 투자로 인해 다른 부문에 추가로 필요한 취업자 수를 의미한다. 취업계수 An은 일정 기간 생산 활동에 투입된 취업자 수(Ni)를 총 산출액(Xi)으로 나눈 값이며, 한 단위(10억 원)의 생산에 투입된 노동량을 의미한다. K 부문의 산출액이 영향을 미치는 취업 유발 효과를 계산하기 위해서는 K 부문을 외생화할 필요가 있다. K 부문을 제외한 취업계수 행렬을 대각 행렬로 전환하여 생산 유발 효과를 곱하면 식 (6)이 도출된다.

| (6) |

는 K 부문을 제외한 취업계수 행렬을 대각 행렬로 전환한 것이다. Δ Ne는 부문에 10억 원을 투입하여 다른 부문에 유발되는 취업자 수의 증감량, 즉 취업 유발 효과를 의미한다.

4. 결과 및 토론

4.1 수소경제 관련 산업의 정의

한국은행은 5년마다 실지조사를 실시하여 투입산출표의 실측표를 작성하며, 그 밖의 연도에는 연장표를 작성한다. 연장표는 실측표 작성 이후의 산업 구조, 생산 기술 및 가격 변화 등이 반영된 결과물이다. 한국은행이 가장 최근에 발표한 자료는 2015년 실측표를 바탕으로 작성된 2019년 연장표이다. 이 표는 381개 기본 부문, 165개 소분류, 83개 중분류, 33개 대분류로 구성된다.

화력, 원자력, 수력과 같은 한국의 주요 발전원은 투입산출표의 가장 세분된 자료인 기본 부문표에 명시되어 있다. 그러나 본 연구에서 분석하고자 하는 수소경제 관련 산업은 투입산출표에 나타나 있지 않다. 따라서 저자들은 수소경제와 관련된 부문을 먼저 식별한 후 부문을 정의하였다. 앞서 2절에서 다룬 수소경제 활성화 로드맵은 수소 산업의 가치사슬을 생산, 저장, 운송, 활용의 4단계로 제시한다. 따라서 본 연구는 정부의 로드맵에 따라 2019년 한국은행의 투입산출표 기본 부문에서 수소경제 관련 부문을 식별하여 수소경제 가치사슬의 각 단계를 정의하였다.

요약하면 본 연구에서 수소경제 관련 산업은 4개의 독립된 부문으로 제시되며, 그 외 부문은 다시 33개 대분류로 통합된다. 분석에 사용된 투입산출표는 총 37개 부문으로 재구성되었다. Table 1은 2019년 투입산출표의 381개 기본 부문에서 식별된 수소경제의 가치사슬 구성이며, Table 2는 한국은행의 33개 대분류 방식에 따라 재구성된 37개 부문 분류표이다.

4.2 결과

재구성된 투입산출표로 수소경제를 구성하는 4가지 부문이 타 산업에 미치는 경제적 효과가 분석되었으며, 생산 유발 효과, 부가가치 유발 효과, 임금 유발 효과, 취업 유발 효과를 분석한 결과가 각각 Table 3부터 Table 6까지에 제시되었다. 또한 수소경제의 4개 부문별 경제적 효과의 순위가 Table 7에 요약되어 있다.

먼저 수소 생산 단계의 생산 유발 효과는 “9. 1차 금속제품”에서 0.1047, “10. 금속가공제품”에서 0.0913, “7. 화학제품”에서 0.0814 순으로 나타났다. 수소 생산 단계가 금속과 화학 산업에 미치는 영향이 가장 큰 이유는 수소를 생산하는 과정에서 각 산업 제품이 밀접하게 연관되기 때문이다. 예를 들어 석유화학 산업에서는 납사를 분해하는 공정에서 수소를 포함한 가스가 발생하며, 수전해 방식으로 수소를 생산하는 과정에는 니켈, 백금 등 금속 촉매가 사용된다. 세부적인 값에는 차이가 있으나, 이러한 경향은 다른 단계에서도 유사하다. 수소 저장, 운송, 활용 단계의 생산 유발 효과는 “9. 1차 금속제품”에서 0.1327, “6. 석탄 및 석유제품”에서 0.1798, “14. 운송장비”에서 0.1887로 분석되었다.

다음으로, 수소 생산, 저장, 운송, 활용 각 단계의 부가가치 유발 효과는 각각 “20. 도·소매 및 상품중개서비스”에서 0.0334, “10. 금속가공제품”에서 0.0374, “6. 석탄 및 석유제품”에서 0.0451, “14. 운송장비”에서 0.1887로 가장 높게 나타났다. Table 7에서 나타나는 바와 같이 전반적으로 서비스업과 제조업 관련 부문이 고르게 배치된 것을 확인할 수 있다. 일반적으로 “20. 도·소매 및 상품중개서비스” 부문이 저부가가치 업종으로 분류된다는 점을 감안하면, 수소경제의 활성화는 서비스업 구조를 변화시키면서 한국이 우위에 있는 제조업 분야의 부가가치를 창출하리라는 사실을 짐작할 수 있다.

수소경제 전체에서 임금 유발 효과가 가장 큰 부문은 “20. 도·소매 및 상품중개서비스”, “26. 전문·과학 및 기술 서비스” 등 주로 서비스업이었다. 특히 26번 부문은 수소 생산 및 저장 기술 개발에 필요한 전문 인력을 확보하기 위해 영향을 많이 받는 것으로 보인다. 다만 수소 활용 단계는 “14. 운송장비”에서 0.0188로 가장 컸다.

마지막으로 10억 원의 생산 또는 투자로 인해 발생하는 취업 유발 효과는 수소경제 전 단계에 걸쳐 “20. 도·소매 및 상품중개서비스”와 “21. 운송서비스”에서 가장 큰 것으로 나타났다. 또한 “26. 전문·과학 및 기술 서비스”는 수소 생산 및 저장 단계에서 각각 세 번째로 높은 순위다. 이는 학계 및 업계에서 수소 분야의 연구개발 인력 양성 사업이 지속적으로 진행되고 있는 것과도 상응한다.

4.3 토론

분석한 결과는 수소경제의 성장이 국내 경제 전체에 미치는 경제적 효과를 정량적으로 나타낸다. 산업연관분석은 매우 직관적이고 적용하기 쉬운 방법이지만, 산업 간 거래가 단일 표로 요약된 투입산출표를 사용하므로 정부 또는 기업이 수소경제와 관련된 정책 계획 및 투자를 위한 여러 의사결정에 활용하기 용이하다. 다만 국가 재정이 한정되어 있으므로, 정부는 장기적으로 경제 성장을 견인할 산업에 지원을 우선할 것이다.

앞서 언급한 바와 같이, 수소산업은 아직 개척되지 않은 분야이기에 대규모 초기 투자가 필요하다. 하지만 장기적 관점에서 보았을 때 수소경제의 실현은 한국의 경제 기반을 지지하는 제조업 및 관련 산업의 생산 활동을 촉진하여 경제 성장에 기여할 것으로 예상된다. 따라서 저자들은 좀 더 구체적인 정보를 제공하고자 2050년까지 수소경제의 성장 규모를 추가적으로 예측했다.

수소산업은 전 세계적으로 연구 및 상용화를 추진하는 단계에 있다. 그러나 한국의 수소산업만을 분석한 자료는 많지 않다. 따라서 저자들은 3단계에 걸쳐 자료 선정의 우선순위를 두었다. 첫째, 정부의 2019년 로드맵 및 2021년 이행 계획에 제시된 목표치를 인용했다. 예를 들어 수소 생산 시장의 규모는 정부가 2019년 1월에 발표한 로드맵에서 제시한 수소 생산 가격의 목표치에 2021년 공개한 이행 계획에서 제시한 수소 생산량의 목표치를 곱하여 계산되었다. 둘째, 한국 정부가 공식적으로 발표하지 않은 자료에 대해서는 IEA와 수소위원회(Hydrogen Council)의 2019년 이후 자료를 인용했다23-28). 셋째, 위의 자료에서 정확하게 파악하기 어려운 시장의 규모 추정에는 전문가의 의견 및 국내 보고서에서 제시한 예측 자료를 반영했다29,30). 분석 결과는 Table 8에 요약되어 있다.

The expected market size of hydrogen economy in South Korea over the period 2030-2050(unit: 100 billion Korean Won)

Table 8은 수소 산업의 가치사슬별로 시장 규모가 어떻게 변화할 것인지를 보여준다. 특히 수소 활용 단계는 2050년 약 31조 원으로 전체 비중의 43.5%를 차지할 것으로 예상된다. 그러나 2023년 주요 R&D 예산 중 수소 활용을 제고하기 위한 예산 비중은 적은 편이다. 또한 기업들은 수소 분야 육성에 가장 필요한 지원책으로 원천기술 개발 지원을 꼽았다. 따라서 수소경제의 성장 기조를 유지하기 위해서는 장기적으로 시장이 커질 것으로 예상되는 수소 활용 단계에 대한 정부의 재정적 지원과 기술 인력 육성이 동반되어야 할 것으로 판단된다.

반면에 수소 운송 단계는 2050년 약 62조 원으로 전체의 9.9% 수준이다. 이는 운송 단계에 해당하는 수소 파이프라인의 시장 규모 추정에 기존 천연가스 설비를 개조하는 비용이 반영되면서 운송량 대비 운송단가가 감소하기 때문으로 보인다. IEA에 따르면 수소 운송을 위해 가스배관망을 개조하는 비용은 신규 건설비용의 21-33%이다. 다만 Table 6에서 제시한 바와 같이 수소 운송 단계에서 발생하는 일자리는 다른 단계에 비하여 많다. 특히 운송 부문과 전문·과학 및 기술 서비스 부문에 미치는 취업 유발 효과가 큰 만큼, 수소 운송 단계는 정부가 목표로 하는 일자리 창출에 도움이 될 것으로 판단된다.

5. 결 론

본 연구는 산업연관분석을 이용하여 수소경제의 경제적 파급 효과를 4가지 측면에서 정량적으로 분석하였다. 가장 최근에 발표된 2019년 투입산출표에 수소경제 관련 산업이 명시되어 있지 않으므로 저자들은 정부의 로드맵에 제시된 수소산업 가치사슬 4단계를 바탕으로 산업을 식별했다. 또한 수소경제에 대한 생산 혹은 투자가 경제 전체의 생산, 부가가치, 임금, 취업에 미치는 영향을 분석하기 위해 수요 유도형 모형을 이용했다.

분석 결과 수소경제 전 단계에 걸쳐 유발되는 경제적 효과가 가장 큰 단계는 수소 운송이며, 가장 적은 단계는 수소 생산이었다. 특히 수소 운송 단계는 취업 유발 효과가 매우 큰 것으로 나타났지만, 2050년 수소 운송 시장은 전체 비중에서 가장 작은 부분을 차지한다. 물론 산업을 영위하는 데 필수 요소인 만큼 산업 전체에서 운송 부문이 유발하는 경제적 효과는 비교적 높은 순위에 있다.

미래 수소경제의 규모는 ’2030년 19조 9천억 원, ’2040년 45조 6천억 원, ’2050년 71조 2천억 원으로 예측되었다. 특히 수소 활용 단계는 시장 전체에서 가장 큰 비중을 차지하는 것으로 나타났다. 따라서 정부는 앞으로 수소 활용 시장에 대해 재정 지원과 인력 육성을 시행해야 할 것이다. 즉 수소경제 활성화를 통해 정부는 양질의 일자리 창출과 경제 성장을 동시에 달성할 수 있을 것이다.

본 논문은 세 가지 측면에서 의미가 있다. 첫째, 많은 연구에서 산업연관분석을 에너지 분야 연구에 적용했지만, 저자들이 아는 범위 내에서 이 연구는 2050년까지의 수소경제의 규모를 예측하고 경제적 효과를 분석한 첫 시도이다. 둘째, 본 논문은 정책 결정자들에게 의사결정을 위한 근거를 제공한다. 셋째, 향후 수소산업의 성장을 목표로 하는 타 국가에서 본 연구와 유사한 연구가 수행된다면, 본 연구 결과와 비교하여 유의미한 시사점이 도출될 수 있다.

Acknowledgments

본 연구는 2022년도 정부(교육부)의 재원으로 수소융합얼라이언스의 지원을 받아 수행된 연구임(2022수소연료전지-004, 수소연료전지 혁신인재양성사업).

References

-

G. Chen, X.. Tu, G. Homm, and A. Weidenkaff, “Plasma pyrolysis for a sustainable hydrogen economy”, Nature Reviews Materials, Vol. 7, 2022, pp. 333-334.

[https://doi.org/10.1038/s41578-022-00439-8]

-

V. A. Goltsov and T. N. Veziroglu, “From hydrogen economy to hydrogen civilization”, International Journal of Hydrogen Energy”, Vol. 26, No. 9, 2001, pp. 909-915.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/S0360-3199(01)00045-3]

-

J. O'M Bockris , “The origin of ideas on a Hydrogen Economy and its solution to the decay of the environment”, International Journal of Hydrogen Energy, Vol. 27, No. 7-8, 2002, pp. 731-740.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/S0360-3199(01)00154-9]

-

S. Milciuviene, D. Milcius, and B. Praneviciene, “Towards hydrogen economy in Lithuania”, International Journal of Hydrogen Energy, Vol. 31, No. 7, 2006, pp. 861-866.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhydene.2005.08.005]

-

U. K. Mirza, N. Ahmad, K. Harijan, and T. Majeed, “A vision for hydrogen economy in Pakistan”, Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, Vol. 13, No. 5, 2009, pp. 1111-1115.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2008.08.005]

-

G. Glenk and S. Reichelstein, “Economics of converting renewable power to hydrogen”, Nature Energy, Vol. 4, 2019, pp. 216-222.

[https://doi.org/10.1038/s41560-019-0326-1]

- International Energy Agency (IEA), “Net Zero by 2050: a roadmap for the global energy sector”, IEA, 2021. Retrieved from https://www.iea.org/reports/net-zero-by-2050, .

- Korea Ministry of Trade, Industry and Energy (MOTIE), “Roadmap to vitalize the hydrogen economy”, MOTIE, 2019. Retrieved from https://www.motie.go.kr/motie/py/td/Industry/bbs/bbsView.do?bbs_cd_n=72&cate_n=1&bbs_seq_n=210222, .

-

S. Y. Lim and S. H. Yoo, “The impact of electricity price changes on industrial prices and the general price level in Korea”, Energy Policy, Vol. 61, 2013, pp. 1551-1555.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2013.06.129]

-

H. Garrett-Peltier, “Green versus brown: comparing the employment impacts of energy efficiency, renewable energy, and fossil fuels using an input-output model”, Economic Modeling, Vol. 61, 2017, pp. 439-447.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econmod.2016.11.012]

-

Y. Lechón, C. de la Rúa, I. Rodríguez, and N. Caldés, “Socioeconomic implications of biofuels deployment through an input-output approach. A case study in Uruguay”, Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, Vol. 104, 2019, pp. 178-191.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2019.01.029]

-

M. Ram, A. Aghahosseini, and C. Breyer, “Job creation during the global energy transition towards 100% renewable power system by 2050”, Technological Forecasting and Social Change, Vol. 151, 2020, pp. 119682.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2019.06.008]

-

F. Luo, Y. Guo, M. Yao, W. Cai, M. Wang, and W. Wei, “Carbon emissions and driving forces of China’s power sector: input-output model based on the disaggregated power sector”, Journal of Cleaner Production, Vol. 268, 2020, pp. 121925.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.121925]

-

J. H. Kim, S. Y. Kim, and S. H. Yoo, “Economic effects of individual heating system and district heating system in South Korea: an input-output analysis”, Applied Sciences, Vol. 10, No. 15, 2020, pp. 5037.

[https://doi.org/10.3390/app10155037]

-

J. H. Kim and S. H. Yoo, “Comparison of the economic effects of nuclear power and renewable energy deployment in South Korea”, Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, Vol. 135, 2021, pp. 110236.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2020.110236]

-

D. H. Lee, D. J. Lee, and L. H. Chiu, “Biohydrogen development in United States and in China: an input–output model study”, International Journal of Hydrogen Energy, Vol. 36, No. 21, 2011, pp. 14238-14244.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhydene.2011.05.084]

-

D. Chun, C. Woo, H. Seo, Y. Chung, S. Hong, and J. Kim, “The role of hydrogen energy development in the Korean economy: an input-output analysis”, International Journal of Hydrogen Energy, Vol. 39, No. 15, 2014, pp. 7627-7633.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhydene.2014.03.058]

-

W. Leontief, “Environmental repercussions and the economic structure: an input-output approach”, The Review of Economics and Statistics, Vol. 52, No. 3, 1970, pp. 262-271.

[https://doi.org/10.2307/1926294]

-

R. E. Miller and P. D. Blair, “Input-output analysis: foundations and extensions”, Cambridge University Press, United Kingdom, 2009.

[https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511626982]

-

M. Llop, “Energy import costs in a flexible input-output price model”, Resource and Energy Economics, Vol. 59, 2020, pp. 101130.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.reseneeco.2019.101130]

-

W. K. Jun, M. K. Lee, and J. Y. Choi, “Impact of the smart port industry on the Korean national economy using input-output analysis”, Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice, Vol. 118, 2018, pp. 480-493.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tra.2018.10.004]

-

S. Y. Han, S. H. Yoo, and S. J. Kwak, “The role of the four electric power sectors in the Korean national economy: an input-output analysis”, Energy Policy, Vol. 32, No. 13, 2004, pp. 1531-1543.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/S0301-4215(03)00125-3]

- International Energy Agency (IEA), “The future of hydrogen: seizing today’s opportunities”, IEA, 2019. Retrieved from https://www.iea.org/reports/the-future-of-hydrogen, .

- International Energy Agency (IEA), “Hydrogen”, IEA, 2021. Retrieved from https://www.iea.org/reports/hydrogen, .

- International Energy Agency (IEA), “Global hydrogen review 2021”, IEA, 2021. Retrieved from https://www.iea.org/reports/global-hydrogen-review-2021, .

- International Energy Agency (IEA), “Greenhouse gas emissions from energy data explorer”, IEA, 2022. Retrieved from https://www.iea.org/data-and-statistics/data-tools/greenhouse-gas-emissions-from-energy-data-explorer, .

- Hydrogen Council, “Path to hydrogen competiveness: a cost perspective”, Hydrogen Council, 2021. Retrieved from https://hydrogencouncil.com/en/path-to-hydrogen-competitiveness-a-cost-perspective/, .

- Hydrogen Council, “Hydrogen insights 2021”, Hydrogen Council, 2021. Retrieved from https://hydrogencouncil.com/en/hydrogen-insights-2021/, .

- I. S. Jeong, “ASTI market insight 23”, Korea Institute of Science and Technology Information, 2022. Retrieved from https://repository.kisti.re.kr/handle/10580/16742, .

- Ministry of SMEs and Startups (MSS), “Technology roadmap for SME”, MSS, 2021. Retrieved from http://smroadmap.smtech.go.kr/, .