Characterization of NiO and Co3O4-Doped La(CoNi)O3 Perovskite Catalysts Synthesized from Excess Ni for Oxygen Reduction and Evolution Reaction in Alkaline Solution

2021 The Korean Hydrogen and New Energy Society. All rights reserved.

Abstract

NiO and Co3O4-doped porous La(CoNi)O3 perovskite oxides were prepared from excess Ni addition by a hydrothermal method using porous silica template, and characterized as bifunctional catalysts for oxygen reduction reaction (ORR) and oxygen evolution reaction (OER) for Zn-air rechargeable batteries in alkaline solution. Excess Ni induced to form NiO and Co3O4 in La(CoNi)O3 particles. The NiO and Co3O4-doped porous La(CoNi)O3 showed high specific surface area, up to nine times of conventionally synthesized perovskite oxide, and abundant pore volume with similar structure. Extra added Ni was partially substituted for Co as B site of ABO3 perovskite structure and formed to NiO and Co3O4 which was highly dispersed in particles. Excess Ni in La(CoNi)O3 catalysts increased OER performance (259 mA/cm2 at 2.4 V) in alkaline solution, although the activities (211 mA/cm2 at 0.5 V) for ORR were not changed with the content of excess Ni. La(CoNi)O3 with excess Ni showed very stable cyclability and low capacity fading rate (0.38 & 0.07 μV/hour for ORR & OER) until 300 hours (~70 cycles) but more excess content of Ni in La(CoNi)O3 gave negative effect to cyclability.

Keywords:

Perovskite, LaCoO3 (Lanthanum cobaltite), Oxygen reduction, Oxygen evolution, Catalyst키워드:

페로브스카이트, 산소환원, 산소발생, 촉매1. Introduction

Our society is engaging a clean energy revolution because of climate change crisis, several researches have been made to develop the sustainable energy. Batteries are the most promising energy conversion and storage devices, which can realize the mutual conversion of electrical energy and chemical energy. Among the many different types of batteries marketed so far, lithium-ion technology has dominated the consumer market since its inception by reason of its high specific energy and power density. However, for lithium-ion batteries, several disadvantages concerning safety and price need to be overcome. As one of the proposed post lithium-ion technologies, rechargeable zinc-air batteries have revived interest due to its desirable properties, such as high energy density, high stability, non-explosive risk and environmental benignity. But, for the rechargeable zinc-air batteries, one of the major drawbacks is its low rates of the oxygen reduction reaction (ORR) and oxygen evolution reaction (OER) at the air electrode1-4). To crack this hard nut, one way is to synthesis a catalyst that showed good activity for both the ORR and OER5-8).

Precious metal is regarded as the most efficient bifunctional catalysts for rechargeable zinc-air batteries, especially Pt, but the high cost, relative scarcity and poor durability limit the commercial applications9). Among the potential substitutes for the precious metal-based catalysts, non-precious metal perovskite oxides, that with ABO3 structure, are the promising candidates. Perovskite oxides have flexible physical and chemical properties through partial substitution of the cations at A- or B-site elements to optimize the desired property10,11). Efforts have been made to improve the performance of the ORR and OER by developing effective catalysts, such as La1-xSrxCo1-yFeyO3-δ, Ba0.5Sr0.5Co0.8Fe0.2O3-δ, Sr0.7Ba0.3Fe0.9Mn0.1O3-δ, SrFe0.9Ta0.1O3-δ, Ba0.95La0.05FeO3-δ, Pr0.4Sr0.6CoxFe1-xO3-δ 12-14). Previously, our research group investigated the LaMO3 (M=Co, Fe, Mn and Ni) perovskites as bifunctional catalysts for zinc-air batteries, the results revealed that LaCoO3 had the best comprehensive performance. And Ni powder, as conductive filler for gas diffusion electrodes, could affect the physical properties of the electrodes, thus the ORR and OER activity was influenced15). These researches showed that catalytic activity increased, especially the ORR activity, but the OER activity rarely increase. Literatures indicate that there is a close relationship between specific surface area property and cathode catalytic performance16). However, one major disadvantage of perovskite-type catalysts is low specific surface area. Porous materials, with high surface area, large pore volume and tunable pore size are promising approach to the problems related to low specific surface area17). Deng et al.18) reported in situ hydrothermal synthesis of SBA-15 containing LaCO3 oxides with a high surface area (>300 m2/g), the catalysts had the excellent catalytic performance in methane combustion. To the best of our knowledge, porous perovskite oxides synthesized by one-step hydrothermally method has not been used as a bifunctional catalyst for the ORR and OER in alkaline solution for application to the air electrode in rechargeable Zn-air batteries.

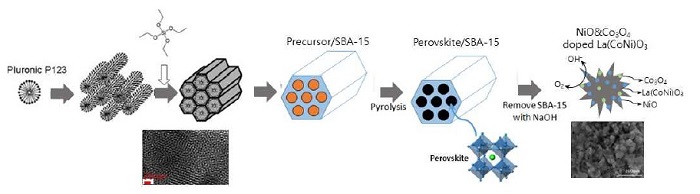

In this work, highly dispersed NiO and Co3O4 in the porous La(CoNi)O3 perovskite oxides (NC-LCNO) were synthesized with excess Ni addition by one-step hydrothermally method and SBA-15 was used as a pore-forming agent, SBA-15 was removed from as-made materials by alkaline washing (Fig. 1). Then the obtained catalysts were tested as bifunctional catalysts for the ORR and OER in alkaline solution applied in rechargeable Zn-air batteries.

2. Experimental

In a typical synthesis of NiO and Co3O4-doped porous La(CoNi)O3 perovskite, P123 were dissolved in 150 mL of 0.1 M HCl solution. Then stoichiometric amounts of La(NO3)3․6H2O and Co(NO3)2․6H2O, excess of Ni(NO3)2․6H2O and citric acid (molar ratio of metal/citric acid=1/3) were added to the solution with continuous stirring. Exact atomic ratios of La, Co and Ni were listed in Table 1. Finally, tetraethyl orthosilicate (TEOS, Aldrich, St. Louis, USA) and PEG400 (polyethylene glycol, Aldrich) were added, and the mixture was stirred for 1h. And then, it was transferred to a Teflon-lined autoclave for hydrothermal reaction at 90°C for 48 hours. After being dried, the obtained materials were well ground, and calcined at 700°C for 6 hours. The silica in the sample powder was removed in 2M NaOH solution for 24 hours and then washed twice with deionized water4). Sample's names were denoted to LCO (LaCoO3) and LCNx (x equals to atomic ratio of excess Ni).

The physical and chemical properties of samples were characterized by X-ray diffraction (XRD, PANalytical, EMPYREAN), field emission-scanning electron microscopy (FE-SEM, SU8220, Hitachi, Tokyo, Japan), X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS, JEM-ARM200F, JEOL, Tokyo, Japan) and their surface areas were measured using a BET method (BELSORP-MAX, MicrotracBEL Corp, Tokyo, Japan).

The bifunctional air electrodes were prepared using the following process: Perovskite powder (20 wt%) was mixed with carbon black (10 wt%, Vulacn XC-72, Cabot, Boston, MA, USA), Ni powder (60 wt%, Inco Co., Toronto, Canada) as the conductive agent and polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE, 10 wt%, DuPont, 60% dispersion) as the binder in the solution of deionized water and ethanol. The mixture was stirred by ultrasound to make slurry, and then dried at 60°C for 12 hours. The mixture was kneaded and rolled to produce a sheet-type catalytic layer with a small amount of extra isopropyl alcohol. This catalytic layer was combined with a wet-proofed carbon paper (ELAT LT1400, Fuel Cell Store, College Station, TX, USA) which was act as a gas diffusion layer by hot pressing at 350°C for 30s to obtain bifunctional air electrode19).

The electrochemical characterization of the bifunctional air electrodes for ORR and OER was conducted in an 8 M KOH solution using a three-electrode system. The working electrode was cut into a round shape which area is 1 cm2. The counter and reference electrodes were used a Pt mesh (Alfa Aesar, Haverhill, MA, USA) and a Zn wire (a diameter of 1 mm, Aldrich), respectively. In the three-electrode system, KOH solution was contact with the catalytic layer and the air went to catalytic layer through the gas diffusion layer (carbon paper). The linear sweep voltammetry (LSV) was conducted to measure current according to cell potential using a potentiostat/ galvanostat (WBCS3000, WonATech Co. Ltd., Seoul, Korea). The cell potential was scanned at a scan rate of 1 mV/s for 20 times between 0.8 and 2.5 V (vs. Zn/Zn2+), which were assigned to -0.413 and 1.287 V vs. standard hydrogen electrode20).

3. Results and discussion

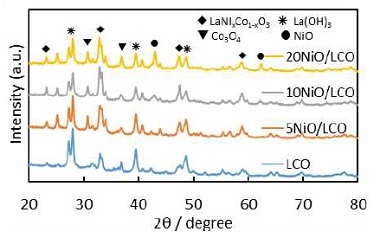

The crystal structure of the synthesized oxides, LCO and LCNx (x=0.2, 0.4, and 0.8), was characterized by X-ray diffraction, the results were presented in Fig. 2. It shows that for all samples, characteristic reflection peaks ascribed to the rhombohedral perovskite phases, which are well in agreement with the standard JCPDS card No. 54-0834, are dominant in the XRD patterns. It is well known that both Co3+ and Ni3+ can serve as B site ions to form ABO3 perovskite oxides. In this work, since the proportion of total molar amount of possible B site ions (Co3+ and Ni3+) to the A site ions (La3+) was over 1.0, the B site ions could be theoretically either Co3+, Ni3+ or both of them. The difference of the B site ions may result in some shifts of the corresponding diffraction peaks. The strongest diffraction peak for perovskite oxides which is located at around 33o was shifted to lower 2θ value with an increase of the nickel concentration, as shown in the right magnified figure of Fig. 2. These shifts of the diffraction peak suggest the formation of B site substituted perovskite oxide of LaCo1-xNixO3, due to the replacement of Co with Ni would lead to a lattice expansion, the ionic radius of Ni3+ is larger than that of Co3+, resulting in the XRD peak shift to lower angles, which is consistent with the previous reports21). Meanwhile, the substitution of Ni for Co will inevitably lead to separation of some Co ions from the perovskite lattice. The Co or Ni oxide species could be formed on perovskite and dispersed22). However, we couldn't measure the quantities for the substitution of Ni to Co site, and the formation of NiO and Co3O4 because of very complicate analysis. The average crystalline sizes of NiO, Co3O4 and perovskite in different samples are calculated by the Scherrer equation and listed in Table 1. It shows that the crystalline size of NiO increases with the increase of Ni contents and small crystalline size may be benefit for the electrochemical performance. The crystalline size of Co3O4 and perovskite was not affected by the different of Ni concentration.

When excess Ni precursor was added to the catalysts, the formation of NiO and Co3O4 were affected by the Ni content significantly. As the Ni contents increase, the peak intensities of those compounds become more and more obvious. Also, the characteristic peaks of La(OH)3 were observed, on account of that La2O3 reacts with H2O in atmospheric air to generate La(OH)3 during NaOH treatment to remove silica and exposure to moisturized air.

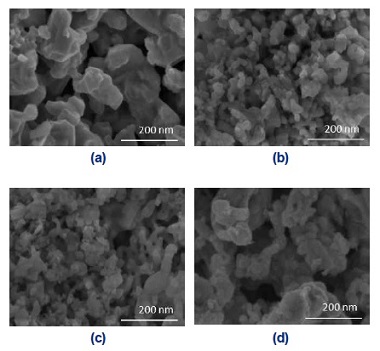

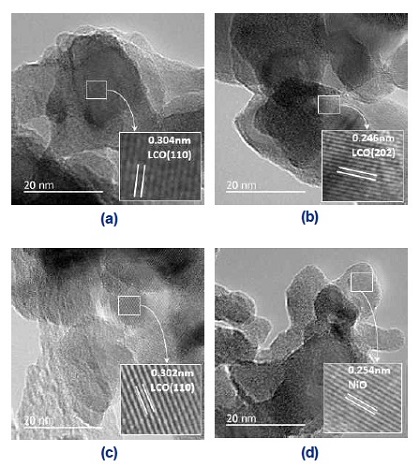

Fig. 3 shows the surface morphology and homogeneity of the LCO and LCNx samples analyzed by the SEM images. It clearly shows that all the catalyst particles are similar to spherical particles with aggregates of smaller nanoparticles which interconnect together to form a similar two-dimensional loose porous network structure, and possess abundant pore structure finally. This is due to the remove of SBA-15, synthesis in the hydrothermal process, abundant pores were formed. From the SEM images, the degree of particle aggregation of LCN0.2 and LCN0.4 are obviously better than the rest two samples. The TEM photographs for the catalysts are demonstrated in Fig. 4. As shown in insect in figures, the samples had well-crystallized layers and the nanoparticles of NiO was found in LCN0.8 in Fig. 4(d). These results means that large amount of excessive Ni addition will cause the accumulation of Ni on the surface.

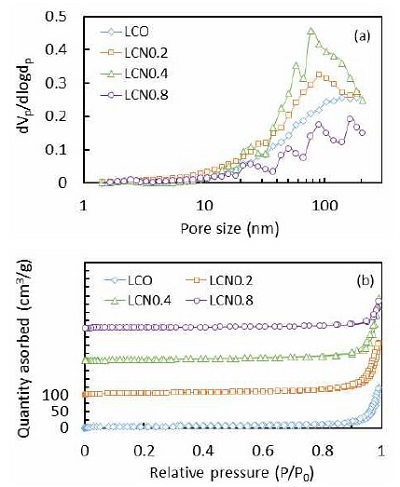

The surface areas and pore size distributions were estimated by N2 adsorption-desorption isotherms and calculated based on the Brunauer-Emmett-Teller (BET) method, as shown in Fig. 5 and listed in Table 1. The BET specific surface area of LCNx synthesized using porous template are much larger than traditional synthesized perovskite oxides. In our previous work4), specific surface area of the traditional LaCoO3 was 2.8 m2/g and the LCO (specific surface area is 18.7 m2/g) in this work was seven times higher than that. For the Ni added samples, the specific surface area of LCN0.4 was 26.7 m2/g which is nine times of traditional synthesized LaCo0.5Ni0.5O3 perovskite oxides23) (specific surface area is 3.2 m2/g). This is mainly due to the implementation of SBA-15, synthesized by P-123 and TEOS, acts as an effective pore-forming agent in the preparation process. Appropriate addition of Ni significantly increased the specific surface area, although more excess Ni addition caused a decrease in the specific surface area, as listed in Table 1. It is expected that smaller particle size with larger surface area may benefit to the electrochemical performance of the catalysts due to the exposure of more active sites to the reactants.

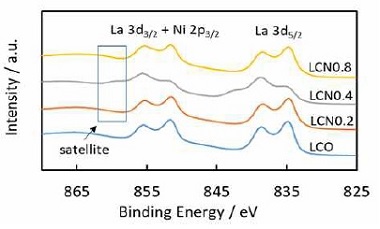

Fig. 6 shows the La 3d and Ni 2p photoemission spectra of LCO and LCNx samples. It clearly show that, in all samples, there are clearly a pair of two separate peaks in La 3d and this implied the presence of the La3+ ion of perovskite24). As La 3d5/2 peak of LCN0.4 around 834.8 eV of binding energy showed a more milder shape and slightly shifted towards higher energy, it indicates the contribution of more surface perovskite oxide species25). The satellite peak of Ni element at about 861 eV, especially for LCN0.4, indicated that the samples contained Ni3+ ↔ Ni2+ phase transition and the formation of LaNiO3 perovskite oxide24). This result suggests that Ni partially substituted Co to form LaCo1-xNixO3. Although the La 3d3/2 peak overlap Ni 2p3/2 peak, according to the position of the La 3d doublet and Ni 2p satellite, these results confirmed the presence of a LaCo1-xNixO3 oxide phase, which is consistent with the results of XRD.

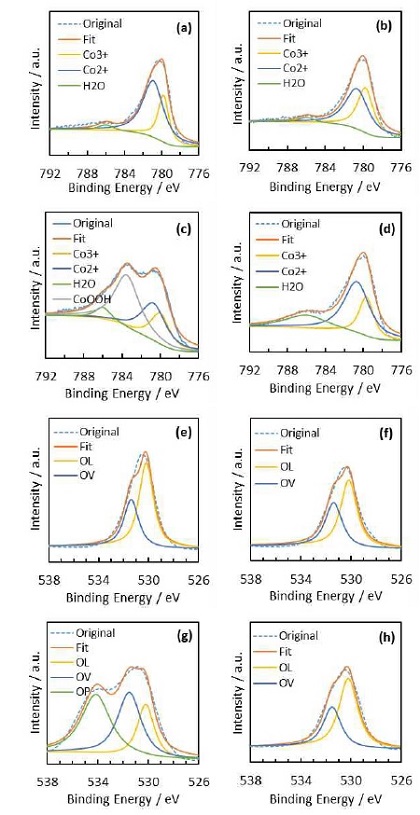

The XPS spectra in the Co 2p3/2 and O 1s regions are shown in Fig. 7. The relative content of the different cobalt and oxygen species estimated from the relative area of these fitted peaks are listed on Table 2. From the atomic ratio detected in the XPS measurement, we can see that the molar ratios of surface La/Co exhibiting a V-shape with the Ni concentration increase, which indicates that appropriate concentration of Ni makes more Co migrate to the surface (LCN0.4 has the highest surface Co percentage). That is, more surface Co ions are exposed and this is crucial for the catalyst with Co (B site cation) as the catalytic active site. As shown in Fig. 7(a-d), the peak located at around 780 eV corresponds to the binding energy of Co 2p3/2, which can be deconvoluted into two peaks with a binding energy of 779.8 and 780.7 eV, being attributed to the Co3+ and Co2+ species20-22). For the LCN0.4 sample, besides the peak located at around 780 eV, there are another two peaks centered at 783.5 and 786 eV which can be ascribed to the CoOOH and Co(OH)2 species24,26,27). However, those were not found in LCN0.8 and we still figure it out why it happened. Previous researchers works pointed out that cobalt (oxy)-hydroxide (CoOOH) is the realistic active species for the OER in alkaline solution28,29). CoOOH is a fundamental and highly important structure-activity correlation for Co-based OER electrocatalysts has been proved30). On the transformation of CoOOH to CoO2 in alkaline medium, CoOOH will form Co-superoxide intermediate, then release of dioxygen from the Co-superoxide intermediate. Through this pathway, CoOOH accelerate the O2 release steps which is the rate-determining step (RDS) of OER31). In other words, CoOOH can effectively adsorb H2O molecules and decrease the OER barrier, resulting in the OER performance improved significantly32). Especially, Chen et al reported that the OER activity of CoOOH was increased with Ni incorporation and four times higher OER current density was achieved with 9.7% Ni content. Because Ni incorporation increased the catalyst's ability to stabilize surface species during the OER, in addition to lowering the charge transfer resistance33). As the amount of Ni addition increases, Ni oxides and hydroxides species will cover the surface and this would decrease the number of highly active sites and lead to a decrease in OER activity33). In this work, the peak intensities of NiO and Co3O4 were increased with increasing Ni amount.

Co 2p3/2 (a-d) and O 1s (e-h) XPS spectra and representative fitting for four different catalysts (a, e) LCO, (b, f) LCN0.2, (c, g) LCN0.4, and (d, h) LCN0.8, respectively

The XPS spectra of the O 1s levels are shown in Fig. 7(e-h). The spectra were fitted by three peaks that corresponded to lattice oxygen species (OL) at around ~530 eV, chemical adsorbed oxygen species (OV) at around ~531.5 eV and physical absorbed oxygen species (OP, e.g., H2O) at around ~533 eV. The OL species with lower binding energy was correlated with oxygen-metal bonds in perovskite. OV species were related to less electron-rich oxygen species, such as hydroxyl and adsorbed oxygen on the oxygen vacancies. The oxygen vacancy makes oxide adsorb oxygen on the electrode surface easier, and lower activation energy required for oxygen reduction34). The more the surface adsorption oxygen concentration, the stronger the surface oxidation ability. This may favor the ORR electrocatalytic process. Table 2 lists atomic ratio of oxygen species of all samples, and the oxygen vacancy proportion in the 4 samples is very close. This is consistent with the results of ORR electrocatalytic performance.

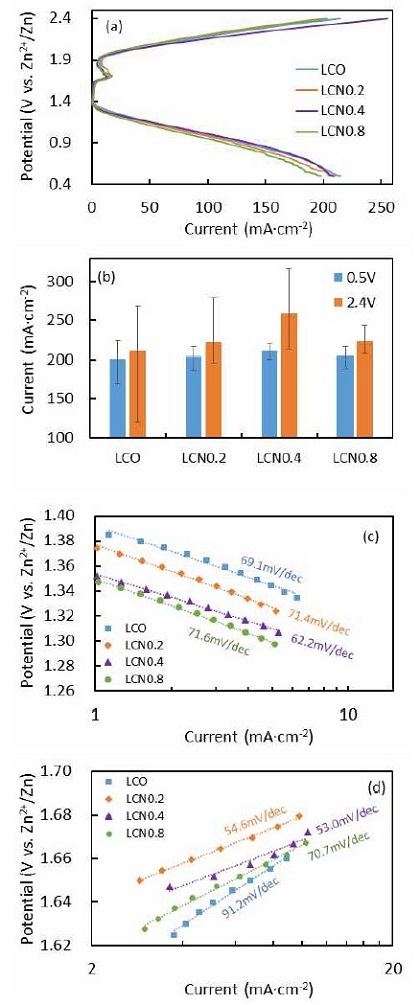

Fig. 8 shows linear sweep voltammograms of LCO and LCNx for the ORR and OER. They were collected after 20 cycles between 0.5 and 2.4 V (vs. Zn/Zn2+). For the ORR in Fig. 8(a, b), the cell performances of the four catalysts were similar and the current densities were very close after 20th cycle (the current densities were around 200-210 mA/cm2), but these results are near 50% increase compared with traditional sol-gel synthesized LaCoO3 perovskite in our previous work4). For the OER, the current density of LCN0.4 at 2.4 V was 14-22% higher than the other samples. Compared with traditional LaCoO3 perovskite4), its OER activity increased by up to 83%. As shown in Fig. 8(c, d), the Tafel slops for ORR in all samples were very close but the addition of excess Ni decreased the Tafel slop for OER. In both ORR and OER, LCN0.4 showed lowest Tafel slops among all samples. These results may be attributed to an enhanced reaction area and diffusion property. Abundant pores and high specific surface area can provide more active site and facilitate the diffusion of reactants for the reaction. In addition to this, the high dispersed Co and Ni oxides species will also promote the activity22).

(a) Linear sweep voltammograms, (b) current of 20th cycle at 0.5 and 2.4 V, and Tafel slopes of (c) ORR and (d) OER for LCO and LCNx electrodes

Based on the above analyses and discussion for XPS, the improved OER performance of LCN0.4 can be ascribed to: 1) the emergence of CoOOH, by appropriate amount of Ni was introduced to the perovskite, boosting the reaction speed of OER, and 2) high specific surface area, abundant pore structure and high dispersed Ni, Co oxide species, providing a large interface and exposing more active site to facilitate catalytic activity.

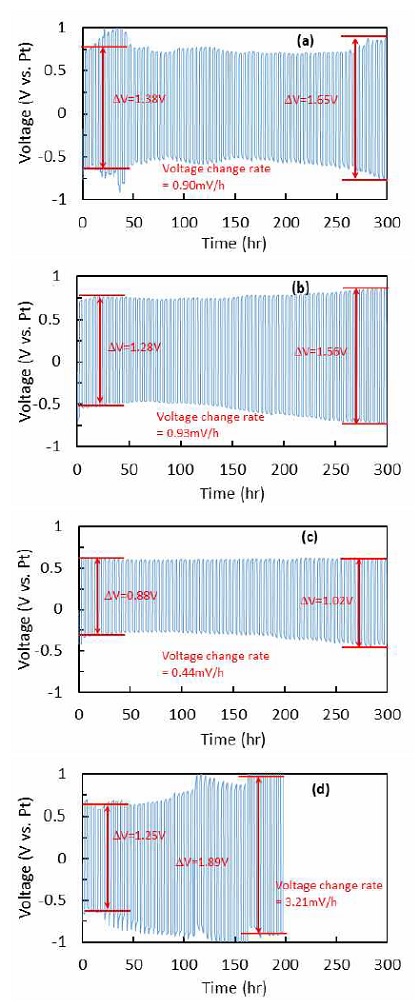

The stability tests of LCO and LCNx for continuous cycles were conducted at current of 20 mA/cm2 for 2 hours of ORR & OER, respectively. As shown in Fig. 9, LCO showed the fluctuation of cell voltage at initial cycling and kept the voltage stable until ~250 hours. And then, the voltage gap was suddenly increased. When excess Ni was added, the stability performance was improved. LCN0.2 showed very stable voltage profiles and slow voltage change with increasing cycling time. Especially for the LCN0.4, there is nearly no change on voltage in 300 hours cycling and the voltage gap between ORR & OER was the smallest, demonstrating the superior stability. But for the high Ni concentration sample, LCN0.8 showed relatively low voltage gap initially comparing with LCO, but it suddenly increased after 25 hours. Table 3 shows the results for initial and final voltages, and voltage change rate. LCN0.2 showed lower voltage gap at initial and final cycles than LCO. Voltage change rate of LCN0.4 after 300 hours cycling showed ~49% lower than that of LCO, and its stability for OER was much better than that for ORR, although LCO showed similar amount of voltage change for both ORR and OER.

Charge/discharge cycling of (a) LCO, (b) LCN0.2, (c) LCN0.4 and (d) LCN0.8 at 20 mA/cm2 with 2 hours per step

4. Conclusions

The porous LaCoO3 perovskites with NiO and Co3O4 as bifunctional catalyst for Zn-air batteries were synthesized using porous template through hydrothermal method, and the change of electrochemical properties in perovskite with excess Ni was characterized for ORR and OER in alkaline solution. By addition of excess Ni, NiO and Co3O4 were found on the surface of perovskites, confirmed by XRD and XPS. Also their surface areas were increased by porous silica template. In electrochemical test, the excellent OER performance (up to 22% increase) was observed at LCN0.4 catalyst with 40% excess Ni in alkaline solution. Moreover, in the cycle performance for ORR and OER at 20 mA/cm2, the addition of excess Ni in perovskite improved stability above 300 hours. The improved electrocatalytic performance might be attributed to the appropriate amount Ni introduction leading to oxides species highly dispersed on the surface, and the optimized composition of Co3+/Co2+ through the formation of cobalt (oxy)-hydroxide (CoOOH), which lead to increase the specific surface area due to porous structure. All these results show that porous LaCoO3 perovskite catalysts with excess Ni may be good candidates as bifunctional catalysts in Zn-air rechargeable batteries.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Ministry of Trade, Industry & Energy (MOTIE), Korea Institute for Advancement of Technology (KIAT) through the Encouragement Program for The Industries of Economic Cooperation Region (P0006134) and the National Research Foundation of Korea Grant funded by the Korean Government (MEST) (2017-R1D1A3B03035157 & 2017-R1D1A3B03032610).

References

-

Y. Li, H. Dai, “Recent advances in zinc–air batteries”, Chem. Soc. Rev., Vol. 43, No. 15, 2014, pp. 5257-5275.

[https://doi.org/10.1039/C4CS00015C]

-

J. Jiang, Y. Li, J. Liu, X. Huang, C. Yuan, and X. W. Lou, “Recent advances in metal oxide‐based electrode architecture design for electrochemical energy storage”, Adv. Mater. Vol. 24, No. 38, 2012, pp. 5166-5180.

[https://doi.org/10.1002/adma.201202146]

-

S. Guo, S. Zhang, and S. Sun, “Tuning nanoparticle catalysis for the oxygen reduction rea ction”, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed., Vol. 52, No. 33, 2013, pp. 8526-8544.

[https://doi.org/10.1002/anie.201207186]

-

J. H. Yang, H. J. Sun, G. Park, J. C. An, and J. Shim. “Synthesis of highly porous LaCoO3 catalyst by nanocasting and its performance for oxygen reduction and evolution reactions in alkaline solution”, J. Electroceram., Vol. 41, 2018, pp. 80-87.

[https://doi.org/10.1007/s10832-018-0165-7]

-

V. Elayappan, R. Shanmugam, S. Chinnusamy, D. J. Yoo, G. Mayakrishnan, K. Kim, H. S. Noh, M. K. Kim, and H. Lee, “Three-dimensional bimetal TMO supported carbon based electrocatalyst developed via dry synthesis for hydrogen and oxygen evolution”, Appl. Surf. Sci., Vol. 505, 2020, pp. 144642.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsusc.2019.144642]

-

R. Kannan, A. R. Kim, K. S. Nahm, H. K. Lee, and D. J. Yoo, “Synchronized synthesis of Pd@C-RGO carbocatalyst for improved anode and cathode performance for direct ethylene glycol fuel cell”, Chem. Commun., Vol. 50, No. 93, 2014, pp. 14623-14626.

[https://doi.org/10.1039/C4CC06879C]

-

S. Ramakrishnan, M. Karuppannan, M. Vinothkannan, K. Ramachandran, O. J. Kwon, and D. J. Yoo, “Ultrafine Pt nanoparticles stabilized by MoS2/N-doped reduced graphene oxide as a durable electrocatalyst for alcohol oxidation and oxygen reduction reactions”, ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces, Vol. 11, No. 13, 2019, pp. 12504–12515.

[https://doi.org/10.1021/acsami.9b00192]

-

S. Ramakrishnan, J. Balamurugan, M. Vinothkannan, A. R. Kim, S. Sengodan, and D. J. Yoo, “Nitrogen-doped graphene encapsulated FeCoMoS nanoparticles as advanced trifunctional catalyst for water splitting devices and zinc–air batteries”, Appl. Cat. B: Environ., Vol. 279, 2020, pp. 119381.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apcatb.2020.119381]

-

Z. Chen, A. Yu, D. Higgins, H. Li, H. Wang, and Z. Chen, “Highly active and durable core–corona structured bifunctional catalyst for rechargeable metal–air battery application”, Nano Lett., Vol. 12, No. 4, 2012, pp. 1946-1952.

[https://doi.org/10.1021/nl2044327]

-

W. G. Hardin, D. A. Slanac, X. Wang, S. Dai, K. P. Johnston, and K. J. Stevenson, “Highly active, nonprecious metal perovskite electrocatalysts for bifunctional metal–air battery electrodes”, J. Phys. Chem. Lett., Vol. 4, 2013, pp. 1254-1259.

[https://doi.org/10.1021/jz400595z]

-

Y. Xue, S. Sun, Q. Wang, Z. Donga and Z. Liu, “Transition metal oxide-based oxygen reduction reaction electrocatalysts for energy conversion systems with aqueous electrolytes”, J. Mater. Chem. A, Vol. 23, 2018, pp. 10595-10626.

[https://doi.org/10.1039/C7TA10569J]

-

Z. Shao and S. M. Haile, “A high-performance cathode for the next generation of solid-oxide fuel cells”, Nature, Vol. 431, 2004, pp. 170-173.

[https://doi.org/10.1038/nature02863]

-

D. Zhang, Y. Song, Z. Du, L. Wang, Y. Li, and J. B. Goodenough, “Active LaNi1−xFexO3 bifunctional cataly sts for air cathodes in alkaline media”, J. Mater. Ch em. A, Vol. 3, No. 18, 2015, pp. 9421-9426.

[https://doi.org/10.1039/C5TA01005E]

-

W. Zhou, R. Ran, and Z. Shao, “Progress in understanding and development of Ba0.5Sr0.5Co0.8Fe0.2O3−δ-based cathodes for intermediate-temperature solid-oxide fuel cells: a review”, J. Power Sources, Vol. 192, No. 2, 2009, pp. 231-246.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpowsour.2009.02.069]

-

K. Lopez, G. Park, H. J. Sun, J. C. An, S. Eom, and J. Shim, “Electrochemical characterizations of LaMO3 (M = Co, Mn, Fe, and Ni) and partially substituted LaNi x M1−x O3 (x = 0.25 or 0.5) for oxygen reduction and evolution in alkaline solution”, J. Appl. Electrochem., Vol. 45, 2015, pp. 313-323.

[https://doi.org/10.1007/s10800-015-0798-z]

-

S. W. Eom, C. W. Lee, M. S. Yun, and Y. K. Sun, “The roles and electrochemical characterizations of activated carbon in zinc air battery cathodes”, Electrochim. Acta, Vol. 52, No. 4, 2006, pp. 1592-1595.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electacta.2006.02.067]

-

J. J. Xu, D. Xu, Z. L. Wang, H. G. Wang, L. L. Zhang, and X. B. Zhang, “Synthesis of perovskite‐based poro us La0.75Sr0.25MnO3 nanotubes as a highly efficient electrocatalyst for rechargeable lithium–oxygen batteries”, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed., Vol. 52, No. 14, 2013, pp. 3887-3890.

[https://doi.org/10.1002/anie.201210057]

-

J. Deng, L. Zhang, H. Dai, and C. T. Au, “In situ hydrothermally synthesized mesoporous LaCoO3/SBA-15 catalysts: high activity for the complete oxidation of toluene and ethyl acetate”, Appl. Cat. A: General, Vol. 352, No. 1-2, 2009, pp. 43-49.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apcata.2008.09.037]

-

K. Kim, K. Lopez, H. J. Sun, J. C. An, G. Park, and J. Shim, “Electrochemical performance of bifunctional Co/graphitic carbon catalysts prepared from metal–organic frameworks for oxygen reduction and evolution reactions in alkaline solution”, J. Appl. Electrochem., Vol. 48, 2018, pp. 1231-1241.

[https://doi.org/10.1007/s10800-018-1245-8]

-

J. Shim, K. J. Lopez, H. J. Sun, G. Park, J. C. An, S. Eom, S. Shimpalee, and J. W. Weidner, “Preparation and characterization of electrospun LaCoO3 fibers for oxygen reduction and evolution in rechargeable Zn–air batteries”, J. Appl. Electrochem., Vol. 45, 2015, pp. 1005-1012.

[https://doi.org/10.1007/s10800-015-0868-2]

-

R. Robert, L. Bocher, B. Sipos, M. Döbeli, and A. Weidenkaff, “Ni-doped cobaltates as potential materials for high temperature solar thermoelectric converters”, Prog. Solid State Chem., Vol. 35, No. 2-4, 2007, pp. 447-455.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.progsolidstchem.2007.01.020]

-

S. Q. Chen and Y. Liu, “LaFeyNi1−yO3 supported nickel catalysts used for steam reforming of ethanol”, Int. J. Hydrogen Energy, Vol. 34, No. 11, 2009, pp. 4735-4746.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhydene.2009.03.048]

-

M. Mousavi and A. N. Pour, “Performance and structural features of LaNi0.5Co0.5O3 perovskite oxides for the dry reforming of methane: influence of the preparation method”, New J. Chem., Vol. 43, No. 27, 2019, pp. 10763-10773.

[https://doi.org/10.1039/C9NJ01805K]

-

M. Mao, J. Xu, M. Zhu, Y. Li, and Z. Liu, “Highly efficient catalytic hydrogen production of Co(OH)2-modified rare-earth perovskite LaNiO3 composite under visible light”, Appl Nanosci, Vol. 10, 2020, pp. 4361-4374.

[https://doi.org/10.1007/s13204-020-01343-9]

-

J. A. Villoria, M. C. Alvarez-Galvan, S. M. Al-Zahrani, P. Palmisano, S. Specchia, V. Specchia, J. L. G. Fierro, and R. M. Navarro, “Oxidative reforming of diesel fuel over LaCoO3 perovskite derived catalysts: influence of perovskite synthesis method on catalyst properties and performance”, Appl. Catalysis B: Environmental, Vol. 105, No. 3-4, 2011, pp. 276-288.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apcatb.2011.04.010]

-

M. C. Biesinger, B. P. Payne, A. P. Grosvenor, L. W. M. Lau, A. R. Gerson, and R. St. C. Smart, “Resolving surface chemical states in XPS analysis of first row transition metals, oxides and hydroxides: Cr, Mn, Fe, Co and Ni”, Appl. Surf. Sci., Vol. 257, No. 7, 2011, pp. 2717-2730.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsusc.2010.10.051]

- J. F. Moulder, W. F. Stickle, P. E'Sobol, and K. D. Bomben, “Handbook of X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy”, Perkin-Elmer Corporation, USA, 1992.

-

H. Wang, W. Xu, S. Richins, K. Liaw, L. Yan, M. Zhou, and H. Luo, “Polymer-assisted approach to LaCo1-xNixO3 network nanostructures as bifunctional oxygen electrocatalysts”, Electrochim. Acta, Vol. 296, 2019, pp. 945-953.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electacta.2018.11.075]

-

J. Yang and T. Sasaki, “Synthesis of CoOOH hierarchically hollow spheres by nanorod self-assembly through bubble templating”, Chem. Mater., Vol. 20, No. 5, 2008, pp. 2049-2056.

[https://doi.org/10.1021/cm702868u]

-

P. T. Babar, A. C. Lokhande, M. G. Gang, B. S. Pawar, S. M. Pawar, and J. H. Kim, “Thermally oxidized porous NiO as an efficient oxygen evolution reaction (OER) electrocatalyst for electrochemical water splitting application”, J. Ind. Eng. Chem., Vol. 60, 2018, pp. 493-497.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jiec.2017.11.037]

-

J. Zhou, Y. Wang, X. Su, S. Gu, R. Liu, Y. Huang, S. Yan, J. Li, and S. Zhang, “Electrochemically accessing ultrathin Co (oxy)-hydroxide nanosheets and operando identifying their active phase for the oxygen evolution reaction”, Energy Environ. Sci., Vol. 12, No. 2, 2019, pp. 739-746.

[https://doi.org/10.1039/C8EE03208D]

-

A. Bergmann, T. E. Jones, E. M. Moreno, D. Teschner, P. Chernev, M. Gliech, T. Reier, H. Dau, and P. Strasser, “Unified structural motifs of the catalytically active state of Co(oxyhydr) oxides during the electrochemical oxygen evolution reaction”, Nature Cat., Vol. 1, 2018, pp. 711-719.

[https://doi.org/10.1038/s41929-018-0141-2]

-

A. Moysiadou, S. Lee, C. S. Hsu, H. M. Chen, and X. Hu, “Mechanism of oxygen evolution catalyzed by cobalt oxyhydroxide: cobalt superoxide species as a key intermediate and dioxygen release as a rate-determining step”, J. Am. Chem. Soc., Vol. 142, No. 27, 2020, pp. 11901-11914.

[https://doi.org/10.1021/jacs.0c04867]

-

J. Huang, J. Chen, T. Yao, J. He, S. Jiang, Z. Sun, Q. Liu, W. Cheng, F. Hu, Y. Jiang, Z. Pan, and S. Wei, “CoOOH nanosheets with high mass activity for water oxidation”, Angew. Chem., Vol. 54, No. 30, 2015, pp. 8722-8727.

[https://doi.org/10.1002/anie.201502836]